A huge Iraqi flag hangs from citadel of Kirkuk. The soldiers of Baghdad were installed when just a week ago y entered without resistance in this multi-ethnic city that Kurds controlled since 2014. At his feet, bazaar has regained its normality after first few days. "The law has been restored," politicians from Arab and Turkmen communities agree. The Kurds are divided. However, ir participation is key to legitimizing open political process and proving that it is in ir interest to work within a united Iraq.

"Baghdad has liberated us from oppression of Kurdish political parties and ir security agencies," proclaims euphoric Tahsim Kahya, from Frente Turkmen. In his opinion, takeover by central government guarantees security of city and rest of oil province.

Learn More- Artillery fighting between Iraqi and Kurdish forces raises tension

- "The referendum has brought biggest disaster in Kurdish history"

- "We just want help getting back to our homes"

A Kurdish bazaar vendor, he disagrees. "There have been houses assaulted and burned." We heard y killed a man. "Here on market nothing has happened, but I'm worried about future," he confides. "I have nothing against Iraqi army, but we know soldiers, y are strangers." Although majority of traders acknowledge that incidents have been limited and that little by little tranquility is coming back, feelings are a skin flower.

After three years in which Kurds have marked passage of province, new rules of game are puzzling for that community. The army, which in 2014 left shamefully its posts before advancement of Islamic State (ISIS, for its English-language), has taken positions in accesses to capital. Within urban perimeter, security has passed into hands of Anti-Terrorist Units (CTS), distinguished by ir black uniforms. But his presence is not oppressive. They are above all flags which makes you feel that control of city has changed hands.

Although Kurdish tricolor has not disappeared, Iraqi ensign, barely visible a month ago, has become omnipresent. It waves not only in military vehicles and bases where forces have been installed, but in squares, lampposts and poles. Often, and that is what most annoys Kurds and many or inhabitants of Kirkuk (mostly Sunni), along with banners with faceless image of Imam Ali or Imam Hussein, two saints of Shia imaginary. They associate m with militias of that confession, after which sense hand of Iran.

"What does Imam Hussein look like with Mam Yalal?" asks Karwan, a young Kurdish university, at confluence of posters that reflects curious alliance that emerged in Kirkuk. Mam Yalal, or Uncle Yalal, is recently deceased Yalal Talabani, founder of Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). A faction of this, led by his firstborn, Bafel Talabani, has accepted as inevitable that central government regains Kirkuk (its political opponents accuse m of having sold city); So he negotiates a participation in provincial government and breaks isolation that independence referendum of last month has submitted to autonomous region.

It doesn't look like that on street. Wher for lack of transparency or propaganda campaign launched by Kurdistan government, Kurds on foot feel that ir leaders have sold m by not presenting a battle to federal forces. In fact, Kurdish bloc that had majority of Provincial assembly (26 of 41 members, including two Turkmen, two Arabs and two independents) has fractured. Fleeing governor and President of House, who led partisans to wishful of union with Kurdistan, representatives of PUK are only ones willing to participate in session that must elect new president and agree governor. But on Monday only five of its seven members had come to parliamentary headquarters, insufficient for, toger with nine Turkmen and six Arabs, to reach a quorum.

The objective of PUK is to place as Governor Rezgar Ali, who already held that responsibility for three regions of Kirkuk that Kurds snatched Saddam Hussein in 1991 and after demolition of it presided over Provincial assembly. That charge goes to a Kurdish is a recognition that this community constitutes majority minority.

"We are not trying to change demographics of city," emphasizes Jalil Ibrahim al Hadidi of Arab Alliance. "It is a question of applying Constitution and laws," he defends visibly satisfied by change of tornadoes.

At moment, Baghdad seems to have managed to avoid sound excesses that militias have committed elsewhere, at least in Kirkuk capital. But Rezgar Ali himself, who defends withdrawal of Kurdish forces to avoid a war, denounces that during first three days "horrible things happened in some places." Among se highlights looting or expulsion of some Kurdish mayors, such as those of Dakuk and Dibbs, locality where oil fields of Avana and Bey Hasan are found. But trust federal army and police. "They are also our armed forces and re are Kurds in m," he says.

"We will need a few days for situation to be reassured because emotions are still exalted," admits Ramla al Obaidi, one of six Arab representatives in Provincial assembly.

Closed liquor StoresÁ. E

The wounds are not visible. The 21 buildings which, according to Kurdish sources, assaulted or burned Shi'a militias on first day of operation, go unnoticed in a city of one million inhabitants. One of m is seat of Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), Kurdish party to which Government of autonomous region accuses of having negotiated delivery of Kirkuk. This Monday several employees are bustled to replace broken crystals, clean and rearrange furniture.

"It was hashed," y say in reference to Shi'a militiamen. However, y are members of Asaib Ahl Al Haq (League of Righteous), who monitor access. "We complained to ir leaders and yesterday, when minister of Interior came, y authorized us to return," y justify with obvious discomfort.

Although re is no news that y were assaulted, liquor stores on Calle Almas also remained closed. Perhaps it is a preventive measure of its owners, in fear that central government would impose dry law promoted by Parliament last year and that Kurdish government has ignored.

Factory fire in Kocaeli: 7 Workers hospitalized

Factory fire in Kocaeli: 7 Workers hospitalized Life to the alleged martial law commander

Life to the alleged martial law commander Turkish Airlines Flight training appointed as President ALPA

Turkish Airlines Flight training appointed as President ALPA Ethnic structures in Iraq live together

Ethnic structures in Iraq live together The Internet giants pay more in Spain, but far from their income

The Internet giants pay more in Spain, but far from their income Is it so hard to say Generalitat instead of generality?

Is it so hard to say Generalitat instead of generality? Mexican Obsession

Mexican Obsession Among all

Among all KYK Scholarship and credit applications have begun

KYK Scholarship and credit applications have begun History in trial

History in trial Use the mirror and propolis against Mantara

Use the mirror and propolis against Mantara Improved the rapid diagnosis of cancer in Metu

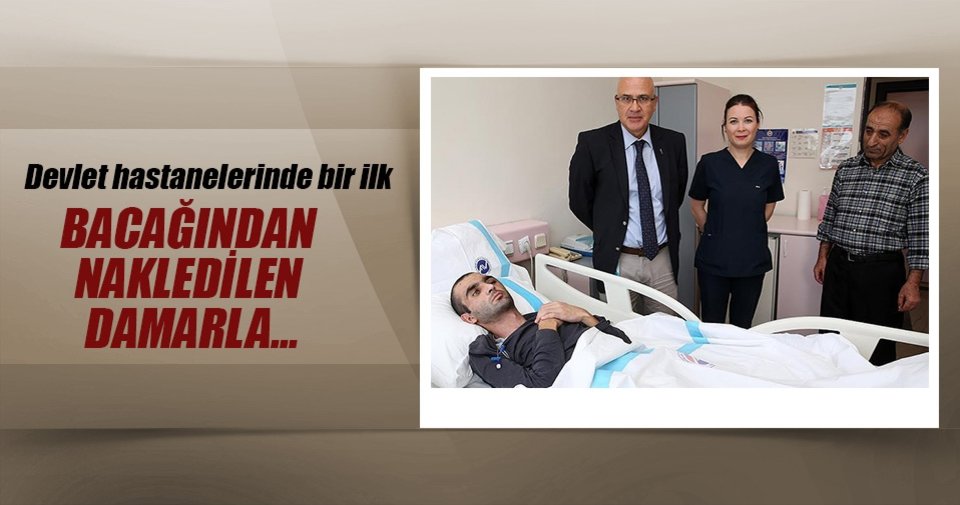

Improved the rapid diagnosis of cancer in Metu He survived a brain aneurysm from his leg.

He survived a brain aneurysm from his leg. Spanish filmmakers call for a forum to address the problem of sexual harassment

Spanish filmmakers call for a forum to address the problem of sexual harassment ' The Walking Dead ' 8: Mercy

' The Walking Dead ' 8: Mercy ' Operación Triunfo ' trusts the millennials to seduce the public again

' Operación Triunfo ' trusts the millennials to seduce the public again The plenary of Parlament to address the answer to 155 will be on Thursday

The plenary of Parlament to address the answer to 155 will be on Thursday Hacienda to dismantle the new Catalan tax agency

Hacienda to dismantle the new Catalan tax agency The government will cease the altoscargos that does not abide by the legality

The government will cease the altoscargos that does not abide by the legality No referee in our tactics

No referee in our tactics 1 Form 3 candidates

1 Form 3 candidates Turkish people on our side

Turkish people on our side Galatasaray's pre-derby silence decision

Galatasaray's pre-derby silence decision Microsoft's new performance monster: Surface Book 2

Microsoft's new performance monster: Surface Book 2 Current location feature came to WhatsApp

Current location feature came to WhatsApp New Volkswagen Polo has been released in Turkey

New Volkswagen Polo has been released in Turkey WhatsApp notification issue and solution on IOS 11

WhatsApp notification issue and solution on IOS 11